Please note that the matter covered in the following article is very subjective and one’s perception of the Indian Budget shall vary on the grounds of the current economic status that one has. The reader is advised to approach the following article without any previous prejudice and with neutrality.

The Indian Budget, formally known as the Union Budget of India, is the country's annual financial statement that outlines government revenues, expenditures, and fiscal policies for the upcoming financial year. It is a crucial document that determines economic priorities, including taxation, subsidies, and public spending.

Presented by the Finance Minister of India, the budget is released on February 1 each year in the Parliament of India, allowing implementation from April 1, marking the beginning of the financial year. This tradition, introduced in 2017, ensures timely policy execution. The budget is classified into two parts: Revenue Budget (taxation and income) and Capital Budget (infrastructure and development expenditures), shaping India's economic trajectory while addressing social and financial challenges.

Just like every year, the budget was presented by the incumbent finance minister, Nirmala Sitaraman, in the Parliament of India on the 1st of February 2025. However, the budget expectations turned out to be absolutely contrary to what the real budget was. The new tax slabs released for the new tax regime were as follows:

- 0to₹4Lakhs–NIL

- ₹4 Lakhs to ₹8 Lakhs – 5%

- ₹8 Lakhs to ₹12 Lakhs – 10%

- ₹12 Lakhs to ₹16 Lakhs – 15%

- ₹16 Lakhs to ₹20 Lakhs – 20%

- ₹20 Lakhs to ₹24 Lakhs – 25%

- Above ₹24 Lakhs – 30%

Besides the absolute makeover of last year’s tax slabs, the government also announced something historic. No income tax payment required to be paid for people with income below 12 lakh. The middle class had finally been brought into consideration by the central government run by BJP. Taxpayers in India can choose between two tax structures: the old tax regime and the new tax regime.

The old tax regime provides various exemptions and deductions, including those for house rent, insurance premiums, and long-term investment schemes, enabling individuals to lower their taxable income. In contrast, the new tax regime, started in 2020, features reduced tax rates but eliminates most exemptions and deductions. While the old system benefits those making strategic investments, the new structure offers a simpler, lower tax alternative for individuals who prefer fewer compliances. The choice depends on one’s financial goals: whether to optimize savings through deductions or opt for reduced rates with minimal paperwork and tax planning.

Many lower middle class families, who had originally stuck to the old regime will now try to migrate over to the new regime to avail this massive tax benefit. However, the scenario of income tax shall remain the same more or less for the families in the other two classes. The Indian population is characterized by a distinct stratification into upper, middle, and lower classes, each with unique income levels, standards of living, investment behaviors, and wealth concentrations.

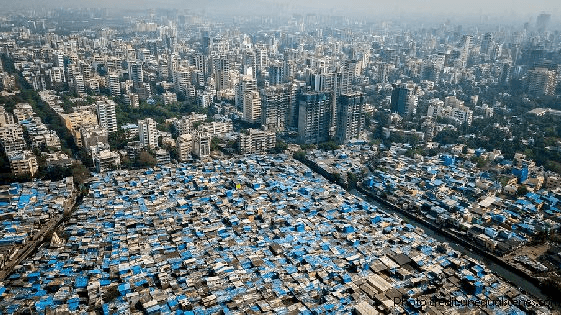

The lower class constitutes a significant portion of India's population. According to a 2021 report by the Pew Research Center, approximately 1.2 billion Indians fall into the lower-income category. This group often struggles with basic necessities, including access to quality healthcare, education, and housing. Their limited disposable income restricts their ability to invest, leading to minimal participation in financial markets. Consequently, wealth accumulation within this segment is negligible, perpetuating a cycle of inescapable poverty.

Estimates of India's middle class vary due to differing definitions. The Pew Research Center identified about 66 million Indians as middle-income in 2021. In contrast, The Economist reported 78 million Indians earning more than $10 per day in 2017, aligning with the National Council of Applied Economic Research's standards. This class enjoys improved living standards, with access to better education, healthcare, and housing. They actively engage in investments such as mutual funds, equities, and real estate, contributing to wealth accumulation. However, the middle class holds a relatively small share of the nation's total wealth, reflecting ongoing economic disparities. The upper class, though a minority, wields substantial economic power. The Pew Research Center identified around 2 million high-income individuals in India as of 2021. This elite group enjoys a luxurious lifestyle, with access to premium healthcare, education, and exclusive amenities. Their investment portfolios are diverse and expansive, encompassing significant holdings in businesses, stocks, real estate, and international assets. Notably, the top 1% of India's population holds a considerable portion of the nation's wealth, underscoring the pronounced economic inequality.

Wealth distribution in India is markedly uneven. According to Oxfam International, the top 10% of the Indian population holds 77% of the total national wealth. Furthermore, the richest 1% of Indians own 58% of the country's wealth. This concentration indicates that a small fraction of the population controls a majority of the nation's resources, while the vast majority holds a disproportionately small share.

India's economic classes exhibit stark contrasts in income, living standards, investment capabilities, and wealth distribution. The lower class faces challenges in meeting basic needs and has limited investment opportunities. The middle class, though growing, still holds a modest share of the nation's wealth. The upper class, despite its small size, commands a significant portion of India's wealth, highlighting the deep economic disparities that persist across the country. A budget that exclusively favors the middle class may initially seem beneficial, as this group drives consumer spending and economic activity, but it’s not. Neglecting the upper and lower classes in fiscal policies can create severe economic imbalances, long-term stagnation, and social instability.

By prioritizing only middle class interests, such a budget could reduce incentives for high-income individuals and businesses to invest in large-scale industries, leading to decreased economic expansion. The upper class, which plays a crucial role in financing startups, infrastructure, and innovation, might shift their wealth abroad due to unfavorable taxation policies or reduced government incentives. This would result in capital flight, slowing job creation and economic growth.

For the lower class, limited public spending on welfare, employment programs, and social security would exacerbate inequality. Many in this segment rely on direct subsidies, rural development projects, and skill enhancement programs to move out of poverty. Without targeted government support, their economic mobility is hindered, widening the wealth gap. The amount of money held by the Government is finite. The increasing capturing of money from such sections of society is common through increases in GST. Lower class indeed will have to suffer to pay the burden of the middle class.

Additionally, inflationary pressures could rise if a middle-class-centric budget increases disposable income without a corresponding rise in production. This would reduce purchasing power across all classes, particularly hurting the lower-income group. A strong and sustainable budget must create balanced growth by supporting investments, wealth creation, and social welfare together. A budget that heavily favors the middle class while ignoring the upper class could discourage self-investments—the capital that high-net-worth individuals inject into industries, real estate, and startups. Many wealthy individuals reinvest their earnings in new business ventures, helping create employment and drive economic expansion. However, if tax policies are skewed against them, they might relocate assets abroad or reduce reinvestments, resulting in capital shortages in key sectors.

Moreover, upper-class individuals contribute significantly to research, development, and infrastructure projects through private-public partnerships. A lack of government incentives could slow technological innovation, limiting industrial progress. Additionally, fewer high-value investments in markets like luxury housing, financial assets, and venture capital funds could negatively impact overall financial stability. Without incentives to reinvest domestically, the ultra-rich might shift focus to global markets, reducing their contributions to India’s GDP. This would ultimately affect the availability of capital for small businesses and industries dependent on high-net-worth investors.

A budget focused solely on the middle class might reduce direct government support for the lower-income population, worsening poverty and social inequality. Many low-income individuals depend on government welfare programs, affordable housing schemes, and food subsidies for survival. If these are deprioritized in favor of middle-class tax benefits, social disparity will increase.

Employment opportunities could also decline, as fewer investments from high-income businesses would mean fewer job openings for low-skilled laborers. The lower class often relies on sectors like construction, manufacturing, and agriculture—areas that require consistent government spending and private investments to sustain employment. A budget that sidelines these sectors will trap the poor in cycles of job insecurity and unstable incomes. Additionally, rising inflation due to increased middle-class spending could disproportionately impact lower-income groups, making essential goods like food, housing, and healthcare unaffordable. Reduced investments in education and skill development would limit social mobility, preventing individuals from transitioning to higher income levels.

Ultimately, economic growth must be inclusive. Neglecting the lower class in a middle-class-focused budget would increase wealth disparity, weakening overall economic stability and long-term development prospects. In totality, we must remember that India is a democratic state. Hardships must not be concentrated to one segment, and a longer vision must be adopted instead of agreementing towards decisions made on the basis of feelings. Years of oppression of the Middle Class does not mandate the drift of such oppression into other sectors, it mandates the killing of the fierce oppression.

Written by Ikshit Sethi